Table of Contents

The Old Static Test Ratings

In the early 2000s, the only indication of strength of a particular bar was its static test rating. There were some high end bars advertised as having 1000lb, 1200lb, 1500lb and 2000lb weight limits. There was no industry standard for measurement. This meant that every manufacturer had the liberty to decide how to measure it or how to estimate it. They went with as high a number as possible, which was the static load, or how much the bar could hold while sitting on a rack without moving and having plates gently loaded up on it, without developing a permanent bend once the weight was removed. Or it was the amount of force in the hydraulic press that pushed against the shaft of the bar. Whatever they decided was fair game.

No matter how they determined this number, it’s an awful way to determine how much weight it can realistically take. A bar set down hard, or even reasonably controlled, on a rack, endures much, MUCH more force from the shock-load than a bar sitting loaded and untouched with that amount of weight, not to mention from the torque produced by the plates at the ends.

So everyone went shopping for, say, a “1500lb test” bar, not aware that there was no standardized testing method that manufacturers adhered to. You would be comparing apples and oranges between manufacturers.

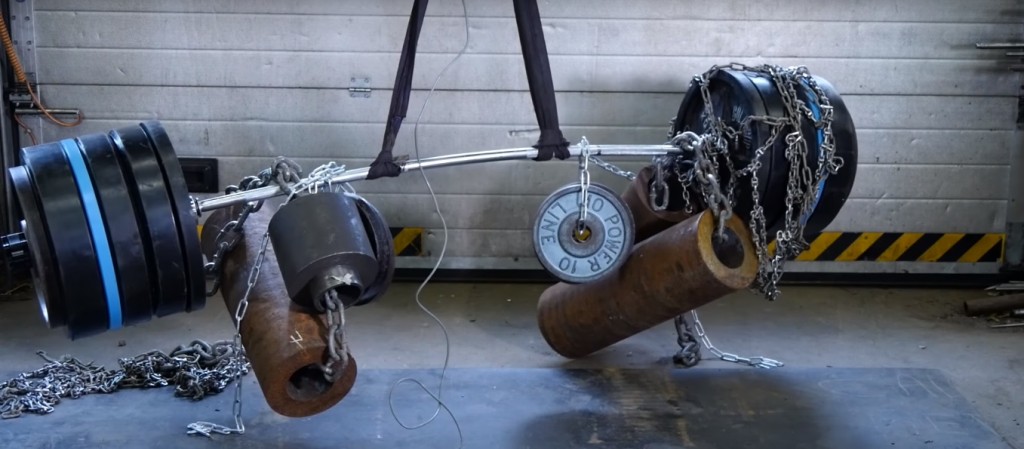

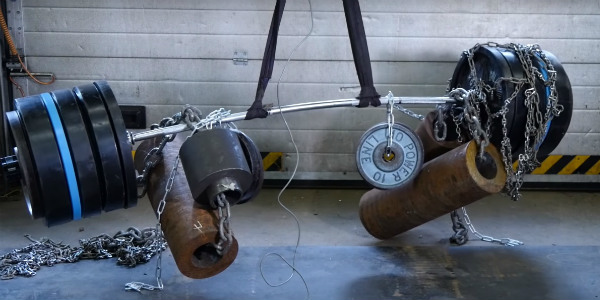

You could always test it out yourself…

Phase 2: Tensile Strength

Eventually, everyone started providing a tensile strength rating of the steel shaft, denominated in pounds per square inch (PSI). That’s much more useful.

Still, a thinner bar such as 25mm or 28mm is weaker in practice than a 30mm bar of the same tensile strength, and there are other factors as we’ll discuss.

Beyond a point, a higher tensile strength isn’t better. Too strong and they will be too stiff for olympic lifts and deadlifts alike. The sweet spot, according to Rogue, is 190,000 to 220,000 PSI. Rogue bars happen to be in the middle of that range at 205,000 PSI. Funny how that works.

Nowadays, with barbell training more popular than ever, most high quality bars are meant to take pretty much any weight you can fit on it and be set down on a rack or dropped with bumper plates. The exceptions are the cheapest bars up to $115 and often included in 300lb weight sets. Any bar closer to $200 is made with better materials, and improving up from there.

The sleeves are also constructed better than ever to withstand being dropped with bumpers all day in a Crossfit gym, which is what really puts them to the test. Manufacturers figured out details such as to double-up on the snap ring or at least use a stronger one, use the right kind of lubrication, and reduce the play in the sleeve fit on the shaft.

The New Rating System

The issue now is how long a bar will last in various lifting environments before the steel shaft suffers too much flexing and will begin to weaken and develop a bend from a forceful drop.

Thus, Rogue invented the F-Scale™, a rating system that will apply to any bar out there, of any brand, if you can get a hold of the right specs to plug into their calculator.

Along with Rogue’s graph, it will tell you how long a bar is expected to last in each type of environment: a home garage gym, powerlifting gym, olympic lifting gym, or Crossfit affiliate.

In years past, the worst a bar would suffer is at an olympic lifting gym, and there just weren’t a ton of those around. Those gyms also would spring for expensive Werksan and Uesaka bars and the like, the very bars that are used in IWF competitions. Nowadays with so many Crossfit affiliates, bars get abused more than ever before. Bars that lasted for decades in a powerlifting gym wouldn’t last 2 years at a busy Crossfit affiliate.

Even though elite powerlifters do lift a lot of weight, the stresses they typically put on a bar are actually not as bad as an intermediate lifter would in his garage, dropping cleans or snatches to the floor every other workout.

Rogue reported something interesting: The more weight loaded on a bar, they say, the less stress is put on a bar as it hits the floor.

This is not exactly accurate. They kind of clarify elsewhere, but what they really found is the stress put on a bar when it’s dropped is the result of how much of the length of the sleeves is supported by the bumper plates.

The bar shaft extends through each sleeve tip to tip, and the more of the sleeve you can support with bumpers hitting the floor, the less the bar will flex. This is easily confirmed with slow motion video. It’s much better to load the bar to the end of the sleeves with econ bumpers, for example, than halfway to the end with the same weight of the thinner competition bumpers, and it isn’t really because of the hardness of the rubber, it’s more to do with how much of the sleeve is unsupported and allowed to flex, thereby putting more stress on the rest of the shaft.

Rogue also asserts that the heavier weights tend to drop more evenly and therefore are easier on the bar. I’ve been visualizing this, and I’m thinking that they generally are right. Even if a more heavily loaded bar is dropped unevenly, it generally will only be a little uneven, and the other side will come crashing down pretty flat with the sleeves nicely supported with all the bumpers.

Bar Finishes and Their Impact on Bar Life

A surprising thing Rogue found out was that the finish/plating on a bar shaft impacted its durability. Not just surface scratches, but literally causing a bar to wear out and bend.

We had caught some hint of this issue in 2002 when Ivanko put out an article about chrome damaging the integrity of a bar through hydrogen embrittlement. They were the only ones saying this, so I had a hard time knowing what was true. Later I found this article saying that baking on the finish is what prevents this from happening.

Does everyone bake on the chrome long enough or soon enough? I don’t know.

Other finishes, Rogue reports, are all good and don’t have the effects of chrome. They mention bare steel, zinc plating, and cerakote. No mention of stainless steel, black oxide, or manganese.

Abrasion Blasting the Bar Improves Life

They found that media blasting, which seems to mean blasting it with either sand or shot or something else to rough it up, extends the life of the bar.

Thanks to our reader Mark for explaining this to me further. The blasting knocks the molecules of the steel out of alignment, so that when a micro-crack begins, it is prevented from continuing further by the misaligned molecules. If the molecules were left aligned, the cracks could go further, allowing for a permanent bend to develop in the bar in response to the stress

Plus, Rogue goes beyond that, saying that while blasting it helps, they’ve got a special process they call Rogue Work Hardening that makes it even better. That’s secret, so not only are the effects mysterious, the process is too.

How to Use the F-Scale to Determine Bar Durability

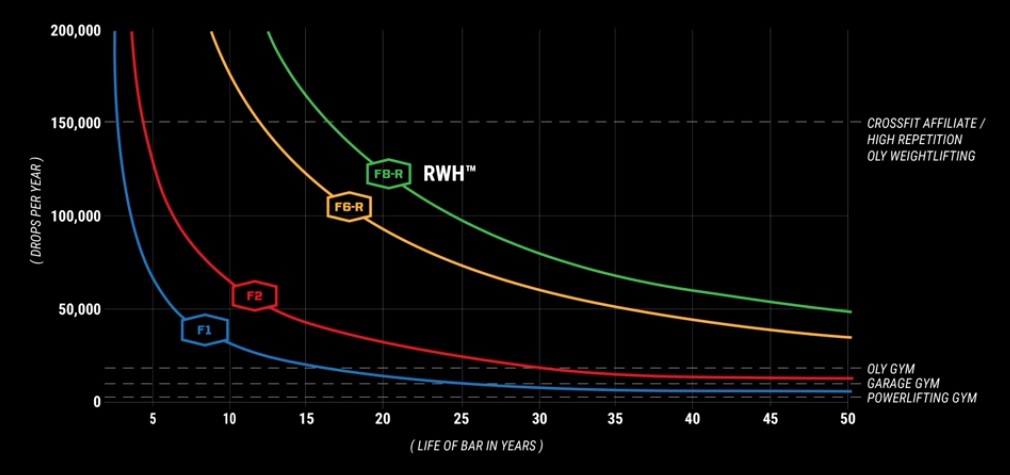

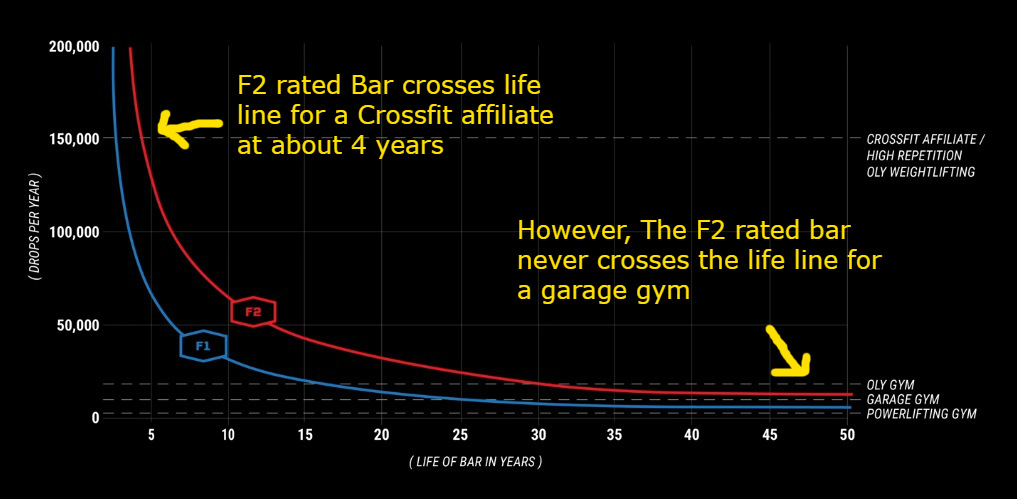

Once you have the F-rating, either from Rogue’s site for their own bars or by plugging it into their calculator for other brands of bars, see their chart below.

Here’s how to read the chart…

The labels on the right side of each horizontal line, for Crossfit Affiliate, Olympic Gym, etc, directly correspond to the labels on the left. Therefore, at a Crossfit affiliate they estimate 150,000 drops per year. That’s certainly on the high end for a busy affiliate, but ok.

Now say you have an F2 rated bar. Follow the red line…

As you can see, the red line for F2 crosses the horizontal “life line” for a Crossfit affiliate in 4 years. That’s how long they suggest an F2 rated bar will last at a Crossfit affiliate.

Notice also that the red line never crosses the line for a garage gym, even after 50 years. Basically it means that as a single user who can only do so much lifting per week, you’re not going to ever wear out an F2 rated bar. Even an F1 rated bar, denoted by the blue line, they suggest will last 25 years in a garage gym.

Will It Catch On?

From Rogue:

Our hope is that the F Scale™ will expand beyond Rogue to allow customers use F Ratings™ when choosing the right barbell for their application regardless of the manufacturer.

Somehow I don’t think it will catch on with other manufacturers.

While the ratings up to F6 can be determined for any brand of bar by Rogue’s calculator on their page, this is shaping up to be sort of like the expensive certification required to say that your bar is IWF or IPF certified.

The issue here is Rogue has a (pending) patent on the new Rogue Work Hardening (RWH™) process so that nobody else can achieve the highest F ratings of F6-R and F8-R. This obviously gives their own brand a huge advantage. Rogue Work Hardening is a secret process done before the finish that apparently improves durability beyond blasting the shaft with beads.

It’s certainly good marketing, putting Rogue firmly in control of issuing the highest ratings and helping to highlight their RWH process as a clear upgrade over their non-RWH bars.

That being said, Rogue is leading the industry with developing new processes like this to make a better bar for us. Rogue dominates the industry in sales, and we should all be glad they’re using some of that profit for R&D like they have already been doing for years.

Your thoughts?

Here’s Rogue’s video announcing all this.

I think the biggest problem with the F scale is that it sets a standard that no one needs, and then says only their bars meet that standard for CrossFit type gyms. That, and when you actually do the math for the number of drops from overhead that they assert happen in a CrossFit gym, it’s extremely unrealistic. Even on the low end of 50k drops a year…that’s 135 drops from overhead, every single day. No gym on earth programs dropping a bar from overhead on every workout, every day.

Ultimately I think they spent a lot of money on barbell testing to come to the conclusion that almost any well made, 190k psi bar will perform well for the life of the bar. In some weird fringe 99.99% fringe case of a gym with a huge number of classes every day, running tons of high rep drop the bar from overhead classes…well they still don’t need anything more than F1. Any decent gym would replace bars after 10 years anyway simply because the coating and knurl starts to wear away and look bad…bending isn’t the first problem.

Yeah, I don’t see the F scale as being a big deal. It would be one of my last considerations, if at all, but then I don’t own a commercial gym. As we thought, it didn’t catch on with others. I’m glad they did the research to find a new way to compare their bars and provide some new information anyway. After all, that’s what I do here, compare stuff based on sometimes questionable criteria!

Why is the yield strength of a barbell rarely mentioned in its specifications, while the tensile strength usually is? I’ve read that yield strength is the real McCoy, and tensile strength, even though a more serious indication than the silly “maximum capacity” of the olden days, is nevertheless useful at best to infer what yield strength might be, as the two tend to be correlated. Why not provide data directly on yield strength?

Yeah I don’t know, not many manufacturers seem to give both, making it hard to compare between them. Most seem to go with tensile strength now, for better or worse. Since originally writing this a couple years ago, it looks like my prediction was right (I think most people were saying the same thing) about the F-rating not catching on among any other manufacturers.

“I don’t get it, but they found that media blasting, which seems to mean blasting it with either sand or shot or something else to rough it up, extends the life of the bar. Someone want to explain this to me?”

Media blasting will work harden a metal. Think of the metal as a network of atoms that form a fairly consistent pattern (crystalline lattice). If a crack goes through a this network it will often continue until is hits an obstruction or variation in the pattern. These obstructions are usually in the form of what is called dislocations (of the crystalline lattice). So more dislocations can make for a stronger harder material that resists damage.

When you media blast steel (for example shot peening) it creates more dislocations as the media and metal collide, think of the impacts as knocking the atoms out of alignment. This will case harden the metal as only the outside is exposed to the work hardening. In bending the max stress on a bar or beam is on the outside of it so case hardening will help against bending. Other work hardening such as cold rolling will actually work harden the metal throughout.

I hope this helps. You can always google anything I mentioned for more info.

Excellent, thanks Mark! That makes sense I guess. I’ll do an update to this article soon to add this useful info.